Eggs and Venice

If you thought that this blog’s title weren’t quirky enough, read further.

Unsplash: NordWood Themes

Mid-1850. Venice has become one of the most popular cities, drawing a steady stream of tourists. Many artists made a living by creating and selling views of the city.

Photography by then had become cheaper and easier to produce and gradually supplanted the earlier techniques of etching and lithography.

As controversial as it gets, Carlo Ponti established a photographic studio were many artists converged to study the ever so popular photography, which consisted of both architectural studies of the city’s details and picturesque landscapes.

Carlo Ponti himself was more an entrepreneur than a photographer, so much so that many a photographs had been attributed to him but most likely very few were actually his ownership. He organised large printing, distribution and sale system of photographs and even acquired negatives from other photographers, and sold them under his own name, a customary practice.

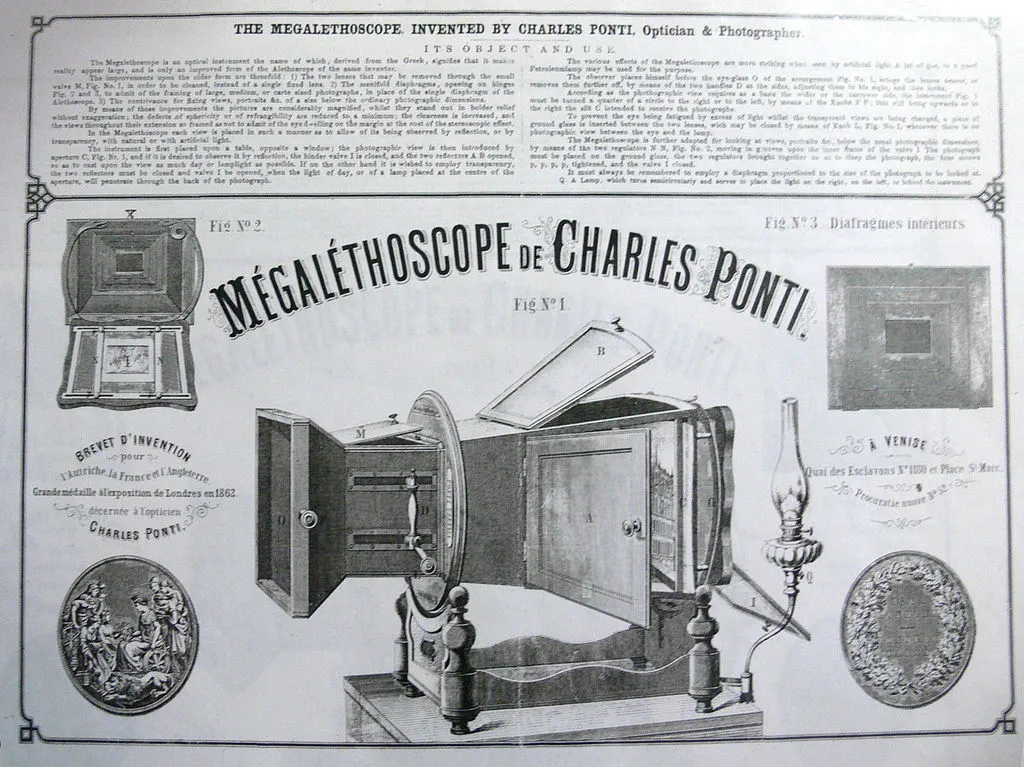

What’s more, Carlo Ponti received the patent to develop and sell unique devices for viewing photographs, such as the Alethoscope, and later on the Megalethoscope.

Collection: Princeton University Library; own photograph

The latter won him a gold medal in the 1862 World Exhibition in London.

This device was a photographic viewer designed to display large prints, viewed first by reflected light and then by transmitted backlight.

The albumen prints were stretched over a frame, with selected areas of the back of the print painted. Increasing the back light made the print translucent enough to allow the colour to show through, causing a visual transformation.

Megalethoscope slide shows a nighttime view of the Ponte di Rialto (Rialto Bridge) over the Grand Canal, Venice, Italy, late 19th century. Megalethoscope slides are viewable either as images that depict day or night scenes, depending on whether they are illuminated from the front or are backlit. (Photo by George Eastman Museum/Getty Images)

Megalethoscope slide shows a scene looking towards the Piazzetta di San Marco, Venice, Italy, late 19th century. Megalethoscope slides are viewable either as images that depict day or night scenes, depending on whether they are illuminated from the front or are backlit. (Photo by George Eastman Museum/Getty Images)

Day lit original photo

First translucent layer

Second translucent layer

Above you can observe marvellous examples of images as displayed by the Megalethoscope of Carlo Ponti.

“ALL THAT GLISTERS IS NOT GOLD.”

- William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

Whether this invention was mere business in disguise, we take a moment to appreciate the beauty and experimentalism of it.

Much like a shadow play (or dare we say light play?), the first image is oftentimes the original photograph lit by frontal daylight, while the second and third are vivid alteration using backlit albumen prints which colours pierce through.

We know what you’re thinking. You held off that question all along but now you must know: what exactly is an albumen print?

As per Wiki, an albumen print is no less than “the first commercially exploitable method of producing a photographic print on a paper using a negative. This method, invented by Louis_Désiré_Blanquart-Evrard circa 1847 used the albumen found in egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper and became the dominant form of photographic positives from 1855 to the start of the 20th century, with a peak in the 1860–90 period”.

This technique was considered as a natural evolution of the salt paper process and unlike it, it could produce intense brownish images.

The most peculiar characteristic of the albumen print was that the image was not embedded in the fibres of the paper, but rather in the albumen layer which allowed for more contrast and brilliance.

Albumen print process (15 easy steps and a reward!)

- Separate the whites of the eggs from the yolks, taking care not to drop any piece of shell into the mix. 12 to 15 eggs yield 500 ml of egg white.

- Transfer and beat the egg whites vigorously.

- Cover the bowl and refrigerate for 24 hours. The froth on the top layer needs to be removed from the whites.

- Weigh 15 g ammonium chloride and mix it with 15 ml distilled water. Then add this mix to the albumen.

- Filter the solution through a coffee filter and store in the fridge for at least a week.

- Coating: place the albumen solution into a tray and place your paper floating on top (be careful not to sink the paper down, as the albumen solution should only coat one side of the paper!). Leave it for 3 minutes, then lift and drain the paper.

- Remove any lumps of albumen with a small needle, popping any bubbles. Hang the paper to dry by its longer edge.

- Double coating: for the sake of brevity, we will skip this part, however quite important one. If interested, refer to “Experimental photography: a handful of techniques” book.

- Sensitising: make a solution of 15% silver nitrate and distilled water. Tape the paper to a support and pour the solution into the centre of the paper and brush it outwards with a non-metallic brush or use a glass rod.

- Allow the paper to dry in darkness.

- Load the paper into a contact printing frame and clip it to the glass to hold in place. Expose the paper to UV light.

- Development: After exposure, wash the print for a few minutes. Water will cause the colour shift from blue to brown or orange.

- Fixing and washing: Fixing is done in two consecutive baths of a 2% solution of sodium thiosulfate. Each bath should last 5 minutes. Washing is takes 20 minutes under running water.

- After the print dried up, it eventually curls. You will need to place it between two pieces of natural cloths and iron it at low temperature for a couple of minutes.

- Tone the print with tea, coffee or even gold salts. Not only it will allow greater variations but also will slow down its early ageing.

We hope you enjoyed this post! Since you were so awesome and read through, here’s a special reward from one of our favourite web.

Check it out! What do you think of the history of the Megalethoscope? Have you ever tried albumen prints? If so, get in contact! We would be happy to see them and feature your work. Notes: Points 9 to 11 are light sensitive and require working into dim light. Disclaimer: Ammonium chloride (NH4CL) and ammonium thiosulfate (H8N2O3S4) are irritant, use caution and wear skin and eye protection while handling.

This blog’s content is based on the book “Experimental photography — a handful of techniques” and “A history of photography”. All featured images are owned by their respective authors and distributed by Getty Images as references.